On the Sunday before Hurricane Florence’s expected arrival in the Carolinas, the pharmacy department at 210-bed Conway Medical Center — 10 miles from the South Carolina coast — placed a “huge” order for next-day delivery, said director Robert Gajewski.

On the Sunday before Hurricane Florence’s expected arrival in the Carolinas, the pharmacy department at 210-bed Conway Medical Center — 10 miles from the South Carolina coast — placed a “huge” order for next-day delivery, said director Robert Gajewski.

The order included antimicrobials, i.v. fluids, and pharmaceuticals to manage “things that might likely happen during a hurricane,” Gajewski said.

Ten vials of snake antivenin were in that order, he said, as were prothrombin complex concentrate, alteplase, tenecteplase, tirofiban, and an assortment of cardiac medications.

Those vials of antivenin were in addition to the 12 or 18 vials that the pharmacy always keeps in stock, Gajweski said.

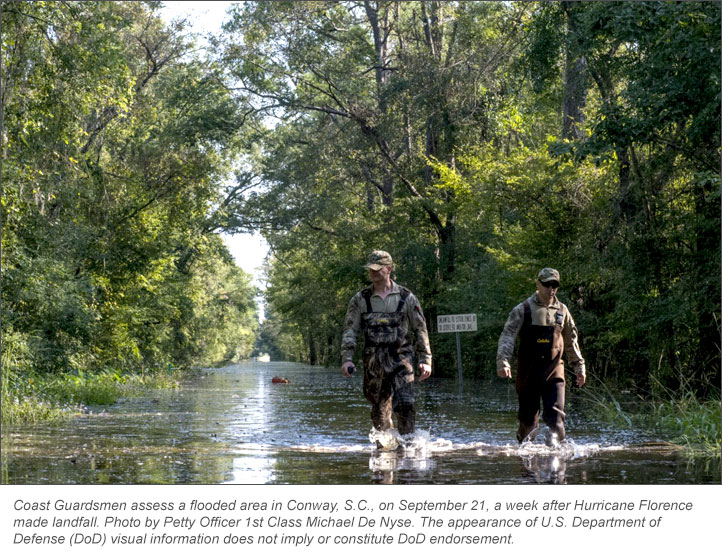

Parts of the city, which sits on the west bank of the Waccamaw River, flooded in 2016 after Hurricane Matthew. In the days since Hurricane Florence made landfall on September 14 about 70 miles northeast of Conway, numerous news reports have shown areas of the city covered in floodwater. President Donald J. Trump visited on September 19.

When interviewed the same day that the president visited Conway, Gajewski said his pharmacy team was preparing for “catastrophic flooding” in areas around the hospital.

“The concern is that roads all around us to and from the hospital are probably going to be inundated with water and ... potentially will be blocked off,” he said.

Gajewski said he ordered the additional prothrombin complex concentrate in case people, in coping with the storm and its aftermath, came to the emergency department for treatment of uncontrolled bleeding. The FDA-approved labeling for the plasma-derived product describes its use for the urgent reversal of the coagulation factor deficiency induced by warfarin therapy in adults with acute major bleeding.

As for the alteplase, tenecteplase, tirofiban, and cardiac medications, they were obtained because of the healthcare situation in Myrtle Beach before, during, and immediately after the hurricane, he said.

Governor Henry McMaster on September 10 ordered Grand Strand Medical Center in Myrtle Beach and Tidelands Waccamaw Community Hospital in nearby Murrells Inlet to evacuate their patients and close down.

“When they closed down Grand Strand,” Gajewski said, “that means that their heart, cath lab, and their open-heart surgery center was now no longer operational.”

Conway Medical Center, which is not licensed for percutaneous coronary intervention or open-heart surgery, had to “gear up” the cardiac catheterization laboratory to support patients in need of those medical procedures, he said. “We’d have to hold them until it would be safe to transfer them, more than likely to the west of us, to Florence, South Carolina.”

Everything that Gajewski ordered from wholesaler AmerisourceBergen Corporation arrived, he said.

The driver, he said, described negotiating detour after detour in a journey that took several hours longer than usual.

During the height of the hurricane, the hospital — which normally schedules sufficient employees to care for 120 patients — had 147 patients, including some from Grand Strand Medical Center, Gajewski said.

About a half-dozen members of the pharmacy staff stayed in the hospital during the hurricane, which released “buckets and buckets of rain” but lower-than-expected winds, he said.

Gajewski stayed at the hospital on a cot in his office on the night that Hurricane Florence arrived. His assistant director stayed the next night. Two pharmacists and three pharmacy technicians made use of the department’s conference room. A third pharmacist, whose relative happened to own a nearby hotel, stayed there. The pharmacist working the night shift housed in the Sleep Lab.

The pharmacy technicians, all women, “created their own space in the conference room” by moving the table and chairs and positioning two cots and an air mattress, Gajewski said.