When three pharmacy students at Binghamton University in New York needed ideas for a project about the opioid epidemic, Bennett Doughty knew how they could use their skills: Training fellow students to recognize the signs of an overdose and administer lifesaving naloxone.

Doughty, a clinical assistant professor in Binghamton’s School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences, worked with the students on a three-year pilot project to teach more than 1,600 participants, mostly university and high school students in upstate New York, about opioid use disorder and naloxone use.

“Pharmacists understand the role naloxone serves,” said Doughty, who also runs the Opioid Overdose Prevention Program on campus.

Though drug use rates among adolescents have remained stable, overdose deaths surged in recent years as illicit, and powerful, fentanyl contaminated drugs such as cocaine and counterfeit pills made to look like alprazolam and amphetamine mixed salts. Two-thirds of those who died had at least one bystander present, most of whom provided no overdose response, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Amid reports of student overdoses and growing community pressure, campus leaders have stepped up efforts to get naloxone in the hands of more students — and at some institutions, pharmacy schools are helping lead the way.

“Pharmacists are the most accessible healthcare providers,” said Yingsi Fang, one of the three Binghamton pharmacy student trainers, who this year begins her postgraduate year 1 (PGY1) residency at UPMC Presbyterian in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. “We are a trusted profession where people already get their medications and their vaccines.”

Pharmacy professor Lucas Hill led one of the earliest campus initiatives, starting in 2016, to prevent opioid overdose deaths at the University of Texas (UT) at Austin. Hill, who had worked on opioid-related research projects as a resident, helped start UT’s overdose training and naloxone distribution for residence hall staff and campus police. He and two pharmacy students also developed a student service training program that has had a lasting impact beyond graduation.

“After seven years leading this program, I have heard numerous stories from our graduates about how this experience prepared them to support people at risk of overdose in their pharmacy practice,” he said. “One of our graduates even saved an overdose victim in their pharmacy parking lot.”

In April, the White House Office of National Drug Control Policy launched the first phase of its campaign to educate young people, including college students, on the dangers of fentanyl and the impact of naloxone. In 2021, fentanyl was identified in nearly 80% of adolescent overdose deaths.

National surveys have found opioid use remains relatively low compared to other drug use among college students. A 2022 report from Ohio State University College of Pharmacy found that 6.8% of 58,000 university students nationwide reported misusing pain medications and 14.5% reported misusing stimulants.

The UT group has shared its work at conferences, including a White House Summit hosted by the Office of National Drug Control Policy, and advised other institutions looking to take similar approaches, said Hill. Colleges can no longer afford to be on the sidelines, and Hill has seen reluctance to provide naloxone begin to fade in recent years. “As awareness of the crisis of opioid-related overdoses has increased among parents,” he said, “we have observed a positive shift in perception among campus decision-makers.”

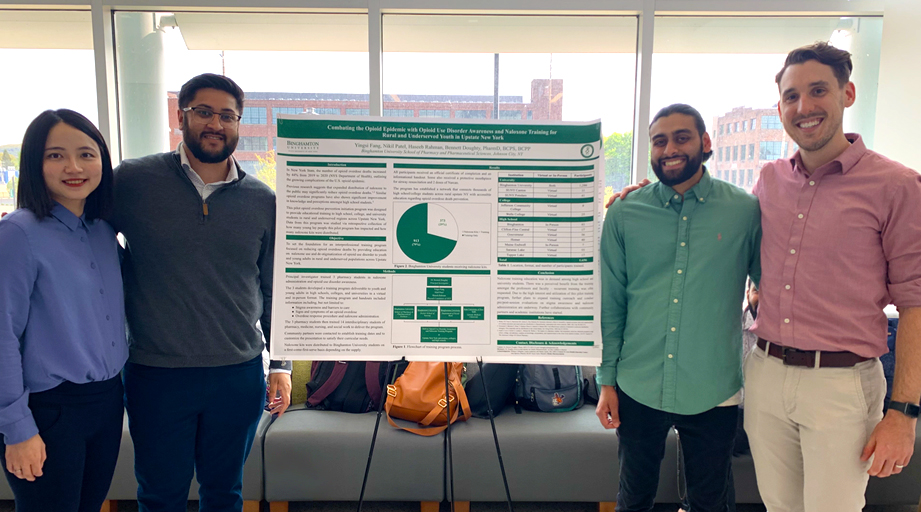

At Binghamton, the three pharmacy students — Fang, Nikil Patel, and Haseeb Rahman — were in their first year when they began talking about a project dealing with opioid misuse. All three were part of The Rural and Underserved Service Track (TRUST) program, a collaboration among the college’s healthcare programs to care for rural and underserved populations.

Binghamton is in Broome County, which was hard-hit by the opioid epidemic and one of the first counties to sign on to the New York State Attorney General’s 2019 lawsuit against large pharmaceutical companies. The students also knew classmates from high school who had developed opioid use disorders.

“This project hit home,” said Rahman.

The trio trained 14 students of pharmacy, medicine, and social work, who in turn could deliver presentations. Between August 2019 and August 2022, the program delivered a mix of in-person and virtual training to 285 high school students and 1,371 college students. The work, which the pharmacy students described in a presentation at ASHP’s 2022 Midyear Clinical Meeting & Exhibition, continues today.

“It just became this massive operation,” said Rahman, now a PGY1 resident at Upstate University Hospital in Syracuse, New York.

Patel, now a PGY1 resident at the VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System in Ann Arbor, Michigan, noted that the project fit in with what pharmacy students learn about practicing at the top of their scope. “This is something we can add to our own plates,” he said, “something that’s so evidently needed in our communities.”

Bethany DiPaula, a professor at the University of Maryland (UMD) School of Pharmacy, has overseen a project in which UMD student pharmacists provided educational materials on naloxone use to local community pharmacists and their patients. She said pharmacists and pharmacy students are in a good position to lead educational efforts because they can talk, in neutral terms, about opioid use disorder (OUD).

“This is a highly stigmatized disorder,” said DiPaula, who also serves as pharmacist representative on the Maryland Addiction Consultation Services. “Providing education from a disease state model is one step toward destigmatizing.”

That is what the Binghamton project leaders aimed to do. Because of the stigma associated with OUD, the first part of the sessions begins with questioning people’s assumptions about who is overdosing, said Doughty. Trainers then talk about the role of genetics in contributing to addiction, just as it does to such diseases as diabetes. Leaders also describe how a person suffering an overdose might look and act, and how best to reassure them.

The point, said Doughty, is to make people comfortable enough to administer the medication. “I can teach someone how to use naloxone,” he said. “But will they?”

Matt Guagliardo, a graduate student in social work at Binghamton, took a training session co-led by Doughty and Rahman. He said he was struck by the comparison of OUD to diseases such as diabetes, a lesson he has used now that he can lead training sessions. He recently provided a session at a Rotary Club meeting, for instance, and he saw people nodding their heads when he used the comparison provided by the pharmacy leaders.

“That was a beautiful explanation,” he said.

While efforts to stem overdoses among students are still relatively new, some leaders are taking note of a few lessons. At UT, Hill and others found that naloxone stored on residence halls went un-used in its first two years, according to research they published in 2020 in the Journal of American College Health. The reasons could be a lack of promotion, they said, or the availability of naloxone at pharmacies.

However, he wrote in an email, “This doesn’t mean that these locations shouldn’t be included, but it does mean that our efforts shouldn’t stop there.”

He said that all their “reported saves” occurred among students who received free take-home naloxone kits that were distributed during training events or available for anonymous pickup from the campus pharmacy. His group recently began allowing anonymous pickup at the campus library as well. “The students who need naloxone,” said Hill, “are those least likely to feel comfortable identifying themselves when obtaining it.”