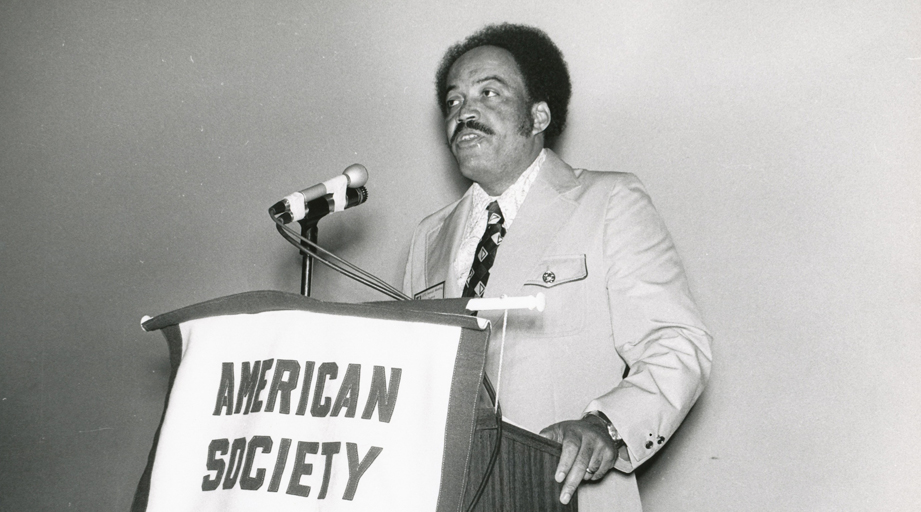

ASHP’s first African-American President Illuminated Career Paths for Black Pharmacists

Wendell T. Hill, Jr. made a career of firsts in pharmacy.

One of the first African Americans to complete a postgraduate residency and earn a PharmD. The first African-American president of the California Society of Health-System Pharmacists. The first African-American president of ASHP.

Hill pursued an ambitious vision not only for his career but also for the profession of pharmacy, forging a path for future generations of African-American pharmacists.

“He was a bright light that came through a lot of darkness to get where he was,” said Christopher Keeys, president and chief executive officer of Clinical Pharmacy Associates/Mednovations and one of Hill’s former students. “He cast his light, invited others in, and was generous. He left a legacy that is larger than himself.”

Breaking Barriers

Hill was born in 1924 in Philadelphia and grew up in New Jersey. His father worked for the railroad and the U.S. Postal Service, and Hill spent his teenage years working summers at his uncle’s pharmacy in Pittsburgh, said his son Wendell T. Hill III.

During World War II, Hill was among the more than one million African American men and women in the armed forces, serving in the U.S. Army in the Pacific and contracting malaria while he was there. When he returned, he joined a large influx of returning African- American service members going to college on the GI Bill. Hill attended Drake University in Des Moines, Iowa, where he met his wife, Marcella Washington Hill, now a retired educator who taught mathematics at the University of the District of Columbia. The couple had two sons, Wendell III, a physics professor in College Park, Maryland and Philip, an orthopedic surgeon in Long Beach, California.

Like many of the African Americans who served overseas, Hill returned unwilling to accept unequal treatment at home. “That was the start of the Civil Rights movement,” said Hill’s colleague, Marcellus Grace, a retired U.S. Naval Reserve captain and former associate dean at Howard University College of Pharmacy and former dean of Xavier University College of Pharmacy.

During his time at Drake, Hill served as both secretary and president of the campus NAACP chapter. He graduated from the school in 1949 and completed his hospital pharmacy residency at the University of Southern California in 1954.

His career took off — fast. Just three years after graduation, he became chief pharmacist at the Orange County Medical Center in California. There he created and served as director of Orange County’s first poison control center. Hill also led the Orange County Comprehensive Health Planning Organization, responsible for overseeing future hospital plans for the community.

Hill’s confidence and willingness to fail help explain how he rose in the ranks of hospital pharmacy despite being among few African Americans in hospital pharmacy, said Wendell T. Hill III.

Orange County in southern California, he recalled, was not a welcoming place for his family during that period. Because communities were segregated, his parents struggled to purchase a house. Hill had to commute 70 miles a day round trip from his family’s home.

Yet Hill III also remembers the tremendous respect his father commanded when he brought him to work at the medical center.

“He was pretty confident in what he could do, and he wasn’t afraid of not succeeding,” Wendell T. Hill III, said.

Rosalyn C. King, retired director of the Pharmacists and Continuing Education Program at Howard University and a colleague of Hill’s, noted that he had a gregarious, outgoing personality and a presence that commanded respect. He was engaged in pharmacy organizations at the state and local levels in California. “Whatever he was asked to do he could always do it well,” said King. “He never sat on the sidelines.”

In 1970, Hill and his family moved to Michigan, where he served as director of pharmaceutical services at Detroit General Hospital and associate professor of pharmacy at Wayne State University. That was where his former resident John Clark met him on the first day of his residency.

“I’d never met anyone like him,” said Clark, director of climate and culture programs and associate professor in the department of clinical pharmacotherapeutics and clinical research at the University of South Florida. Clark noted that Hill was always impeccably dressed, unflappable, and erudite. His office was strewn with books on an array of topics and photos of Hill with his family and many notable people.

“If I did a project and he didn’t like it, rather than criticize me, he’d say: ‘I don’t think you put your best foot forward,’” Clark said. “I was determined to do my best, so I worked a little harder.”

At Detroit General Hospital, Hill pushed his residents to take on more frontline patient care roles and started a clinical pharmacy program, Clark said.

In 1977, Hill became dean at the Howard University College of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences in Washington, DC, a position he held until his retirement in 1994. Wendell T. Hill, III, said his father was very proud to work at Howard and relished the opportunity to give back to the community there. Hill helped the school obtain full accreditation from the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education and established its PharmD program.

Ahead of the Curve

While Hill’s path to ASHP’s top leadership post required persistence — he sought the office twice before being slated — his 1971 election came before other major professional medical associations elected African Americans as presidents. The American Pharmacists Association and the American Nurses Association elected their first African-American presidents in 1979, while the American Medical Association did not elect its first Black president until 1995. Many professional clinical societies had historically excluded or limited the participation of African-American practitioners leading to the formation of African-American-led professional organizations such as the National Medical Association in 1895, the National Pharmaceutical Association (NPhA) in 1947, and the Association of Black Health-System Pharmacists in 1978. Hill also served as president of NPhA in 1992.

As the first African-American president of ASHP and a prominent leader in the profession, he made a lasting impression on generations of African American pharmacists.

Hill helped kindle Clark’s interest in participating in professional pharmacy organizations and introduced him to others in the profession. Grace also recalled looking up to Hill as a role model when he was a student and said it was a point of pride for him to serve on the faculty at Howard alongside Hill.

Keeys and his wife, Sabrina, graduated from Howard during Hill’s tenure. He found Hill approachable, strategic, and supportive. Hill showed a keen interest in the Keeys’ entrepreneurial path to creating pharmaceutical consulting firms.

If he was speaking to you even for a short period you were with him, he would try to connect so there was meaningful discussion,” Christopher Keeys said. “It was intentional that he was listening to mentor and assist in facilitating people’s journeys.”

Valerie Hogue, a 1987 graduate and later a faculty member at Howard University School of Pharmacy, said Hill had observed her potential early in her pharmacy career and helped her develop her strengths. She worked to follow his example.

“I made every effort to emulate his example in my role as professor and academic dean, identifying individual strengths amongst students and faculty and supporting their development through mentoring and professional experiences, said Hogue, now a retired associate dean and professor at Notre Dame of Maryland University School of Pharmacy.

Hill died of cancer in 1995. His son said Hill would have wanted his legacy to be a simple one. “He would want to be remembered as someone who cared, as someone who wanted to be fair, as someone who enjoyed life.” Wendell T. Hill, III, said.

But Hill’s simple legacy, say those who knew him, was profound.

“Without question, Dean Hill broke barriers in the profession,” said Hogue. “He entered practice and excelled at a time when few African Americans were allowed the opportunities to reach their full potential in pharmacy. He made no excuses for the challenges he may have faced professionally but instead made it his responsibility to learn all that he could about the practice of pharmacy and how to improve it.”