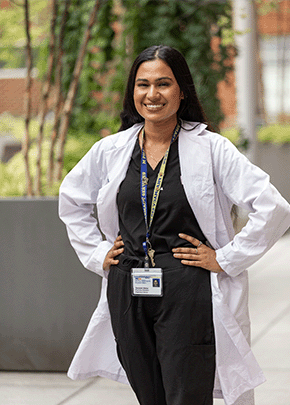

Michael Wolcott

Michael Wolcott was leading last year’s Summer Meetings session on diversity and inclusion when someone spoke up from the audience.

Wolcott was incorrect to use the term “wheelchair bound,” the audience member said. The preferred term is “wheelchair user.”

“Thank you so much,” Wolcott, PharmD, dean for education/chief learning officer/associate professor at High Point University Workman School of Dental Medicine, recalled saying. “They were totally right. And that was all it took.”

Wolcott is tackling the dynamic topic once more as he helps lead this year’s two-part session Getting IDEAS that Matter: Addressing Inclusion, Diversity, Equity, and Access (IDEA) in Pharmacy Practice at the 2023 Summer Meetings & Exhibition in Baltimore. He hopes participants will risk making mistakes – and learning from them – just as he did last year.

“I expect people to come and be uncomfortable in this process and we do set that tone early,” he said. “That’s really what we hope for, an open mind and willingness to lean into that vulnerability.”

Wolcott spoke with ASHP in advance of his Summer Meetings session. What follows is an edited transcript of that conversation:

ASHP: Why are we using the acronym “IDEA?” How’s it different from more familiar acronyms like DEI (diversity, equity, and inclusion)?

Wolcott: Some people will argue that the order you place them in matters. For example, if inclusion is the end goal, you put the “I” first. Even with IDEA, the A has been “access” and “availability.” It’s really just different flavors of what people want to discuss as it relates to bringing people into different spaces and granting them a voice. And helping people understand it’s not just the mere presence of individuals that may or may not look like them but having a space in which they contribute to conversations and decisions.

Can you give some concrete examples of how this could play out in a healthcare setting?

What we’ll do as part of the workshop is walk people through the process of evaluating what it is they’re contributing, how well they think they’re doing in terms of bringing in people who are different, and really developing and understanding how they can apply these strategies within their organization.

What does that look like?

We say, “Let’s start with you. How do you create a space in which people can even talk about these kinds of topics?” We forget that some people feel uncomfortable even starting to have those conversations. It’s really based around what’s called psychological safety, this idea that people feel they can have productive conversations, they can contribute to those discussions, and they can challenge specific things they may encounter. When we think about all the work that can be done around inclusion and belonging it’s huge. We have to start somewhere.

What have you done in your own organization to make having those conversations more comfortable?

We’ve done routine check-ins at the start of meetings. One of my favorites is “If your life were a rollercoaster right now, where would you be on the roller coaster?” Or we’ll ask people for a weather report about how their day is going. “Well, it’s a little cloudy. No, it’s a hurricane.” We ask people to tell stories about their names, favorite childhood meals, and questions that really get to them as people. You learn about people, and you can empathize with them more.

You said earlier that sometimes as a pharmacist you had a hard time with these abstract ideas. Can you talk about that?

When I shifted into the social sciences, it was incredibly uncomfortable. Why do we care so much about all this squishy stuff? We assume that because something is physical and tangible, we can measure it, and it’s more valid than anything else. Versus an emotion, an experience, where it’s harder to understand what’s going on and how that can change based on the specific environment. One of the things we think about in pharmacy is you give a drug, give it at this dose, and you get this effect. But one reason people are becoming more comfortable with dynamic issues is that we’re learning about the influence of genetics. Well, I could give this drug to somebody, and it might not work because they have a different genetic mutation that I don’t know of. I think that’s opened the door to people understanding that, yes, evidence provides you with some sort of statistical probability that this will work out. But it’s not a 100% guarantee.

How long have you been doing this kind of work, and how has the reaction you’ve received changed — or not — over the years?

I’ve been working in this space for just under five years. I identify as a gay man. When I was in pharmacy school, I never had any specific representation I thought was present in that environment. I felt like it was something I couldn’t openly share with people. As I saw a lot of movement with Black Lives Matter and especially now with what we’re seeing around anti-trans and anti-LBGQT-plus type work, I want to be a voice in this space. For some people this is very difficult work, and for others, it’s very easy. Some people say, “I don’t see race, I think of all people as equal.” Yes, but we also live in a society where those factors do come into play. And if we don’t recognize that, it can obscure the challenges.